Christine Benz: Hi, I'm Christine Benz for Morningstar.com. Do investors in index funds tend to make better timing decisions than investors in actively managed funds? Joining me to share some research on this topic is Ben Johnson. He is director of global ETF research for Morningstar.

Ben, thank you so much for being here.

Ben Johnson: Thank you for having me, Christine.

Benz: Ben, in your latest issue of ETFInvestor, you discussed the dollar-weighted returns of index fund investors relative to active fund investors. Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the data, let's discuss what dollar-weighted or cash flow-weighted returns are and how they are different from the published total returns that we all see--the 10-year and five-year returns that are so commonly depicted for funds?

Johnson: To put it as simply as I can, time-weighted returns--the returns that you see on funds' fact sheets, on fund companies' websites--

Benz: Right. Morningstar.com.

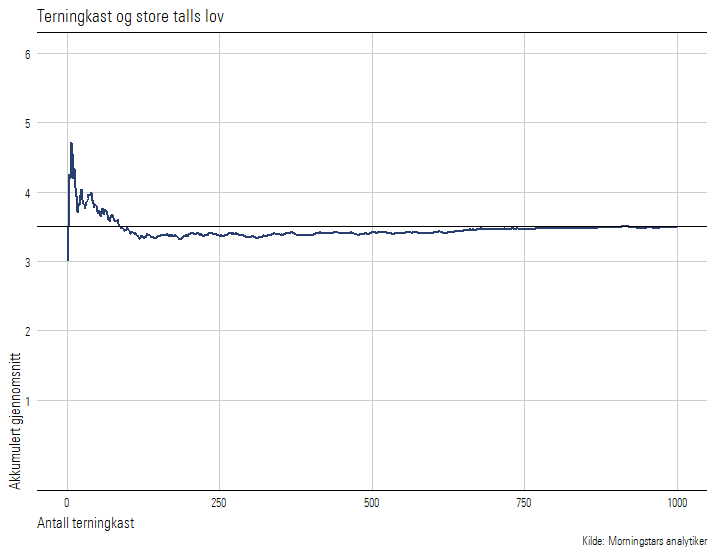

Johnson: … Morningstar.com--tell you how funds perform. Cash flow-weighted returns, Morningstar investor returns, which we calculate, tell you how investors perform. Those latter calculations take into account investors' cash flows, the money flowing into and flowing out of funds over time to see, on average, how has a typical dollar invested in a given fund performed. We can then compare that figure, how investors have performed or the average invested dollar, relative to the fund itself to understand whether or not investors are using funds well, whether they are experiencing as much of the returns that are generated by the fund in that underlying index or the manager as the case might be as possible, or are they falling short, are they falling victims to their own bad behavior.

Benz: If I see a fund's total return, like its 10-year annualized total and it's 8%, that assumes that I bought at the beginning of the period and held on all the way through. With these dollar-weighted or cash flow-weighted returns we are actually factoring in that our investors are coming and going all of the time. They might not be staying the course for these long periods.

Johnson: That's absolutely right. Maybe, I bought and sold and bought back in; maybe I was even just doing something that is typically evident of good behavior which was just regularly dollar cost averaging into that fund. One way or another cash flows are going to create some sort of mismatch between the returns that investors experience and the returns that funds produce over any given period.

Benz: We've been measuring these cash flow-weighted or dollar-weighted returns for a while. We've been looking at them. You looked specifically at the subset of index funds and compared that to investors in actively managed funds. I'd like to talk about what you found, but first, when you were looking at index funds, did you factor in exchange-traded funds or were you just looking at traditional index funds?

Johnson: Exchange-traded funds were excluded from this study. What you find in exchange-traded funds that is absent when you are looking at index mutual funds is that there is a lot of noise in that data. That noise is created by noise traders or just traders full stop and ETFs that aren't going to trade index mutual funds. By virtue of the fact that ETFs are listed on an exchange, they have naturally a much more diverse investor base, and that much more diverse investor base is using ETFs in a number of different ways that one would never think to use an index mutual fund. You might be selling an ETF short; you might be trading it quite frequently, because in many cases, you are seeing a growing institutional user base that's using ETFs in lieu of, say, S&P 500 index futures contracts. The natural rate of turnover in ETFs is much higher given the multitudinous uses of ETFs among, again, a very diverse investor base. We exclude ETFs from this examination to eliminate that noisiness from the analysis.

Benz: Let's take a look at the domestic equity cash flow-weighted returns for index fund investors versus active investors. What you found makes index fund investors look pretty smart. Let's talk about what's going on there, sort of the general finding, and also, I'd like to get your thoughts on why it does appear that the index fund investors have timed their purchases and sales a little better, or maybe a lot better than the active investors?

Johnson: What we've seen in the years that we've been looking at the investor return gap or the behavior gap, if you will--this difference between time-weighted and cash flow-weighted returns through the lens of index funds versus active funds--is that generally speaking, index funds have demonstrated across virtually every category a lower gap, a narrower gap. I would attribute that to a number of different things. I think, first and foremost, is just expectations, that index fund investors go in knowing for well what they are signing up for. They are signing up for market performance less a small fee.

I would also attribute it in part to the fact that index funds, either on an a la carte basis or in context where they are a piece of the pie in, say, a target-date mutual fund, are increasingly present in growing in channels where it's easier for investors to be on their best behavior. 401(k) programs are a perfect case in point, where now especially because target-date funds are qualified default options in those programs, investors are regularly dollar-cost-averaging into those funds, and those funds themselves, the target-date mutual funds that are those default options, are increasingly comprised of index mutual funds. I think this all points toward better behavior and puts sort of guardrails around investors and keeps them sort of sitting tight, if you will, when it comes to investing in index mutual funds.

Benz: Let's talk about the specific time period that you examined as well, because as you noted in your article in ETFInvestor, there is a relationship between dollar-weighted returns and the specific market environment. Let's talk about that and how the generally strong market environment, the interplay between that and this tendency of index fund investors to capture a lot of their fund's returns.

Johnson: It's important to be mindful of the math that underpins these calculations because at best they are a proxy for investor behavior. There are other unique things that are going on that are important to take into account. As you described, what we've seen over the course of the past 10 years has been a massive shift away from actively managed funds, particularly actively managed equity funds, and into index funds and exchange-traded funds.

Part of what we are seeing in terms narrower gaps among index funds is almost to be expected given directionally we've seen cash flows moving into index funds in large amounts and fairly steadily over the course of the past decade, while the market has been trending upward, coming out of the very bottom of the post-financial crisis bear market. Meanwhile, those same dollars have, in many cases, been coming from actively managed funds. As the dollar flows out of an actively managed fund that continues to perform at least well enough because the rising tide has been lifting all ships, the math will naturally make that look like a poor decision and will naturally make the dollar being invested in the index mutual fund look like a good decision by comparison.

Benz: This may not be persistent, that it may be quite dependent on the specific confluence of events that we've seen recently?

Johnson: Absolutely. There will inevitably be noisiness just around this calculation itself that will be influenced in large part by sort of the chosen start and end point for the analysis and also, just what's going on in the prevailing market more broadly speaking.

Benz: That's domestic equity. Let's look at international equity. It's interesting because the picture is pretty different, where the passive investors, the investors in traditional index funds don't look all that smart from the standpoint of timing, at least over the period that you looked at. What's going on there?

Johnson: That's a perfect case in point. It touches back on what we've just described, which is, it's difficult to say? If you unpack that, what it looks like if you zoom in a bit more closely is that there are some really good active managers out there that have had more faithful shareholders relative to their index counterparts. I would caution against painting with broad brush strokes here in saying that any of the learnings applies universally when it comes to understanding what's going on with respect to investor behavior. There are certain areas of the market where investors in active funds have simply just been on better behavior than their counterparts in index mutual funds.

Benz: In terms of how investors should interpret these data, are there any general conclusions that you would offer, things that investors can use to inform their own decision-making?

Johnson: I think it boils down to quite simply, pick a plan and stick to it. Because irrespective of fees and taxes, you name it, what we see and what we are able to quantify with these behavior gaps that we are measuring are penalties that are many, many multiples any run rate fee you are going to pay, be it on an active fund or an index fund, any tax headwinds that you might incur. The chief culprit in investors' shortfall is investors themselves. We've seen the enemy and the enemy is us.

Benz: Great point. Great research. I'm fascinated by this stuff, Ben. Thank you so much for being here to discuss it with us.

Johnson: Thank you for having me.

Benz: Thanks for watching. I'm Christine Benz for Morningstar.com.