Jeremy Glaser: For Morningstar, I'm Jeremy Glaser.

After some recent volatility, stock markets and major indexes are testing record highs again. I'm here today with Matt Coffina, editor of Morningstar's StockInvestor newsletter, to see what his take on valuation is and if any opportunities have opened up.

Matt, thanks for joining me.

Matt Coffina: Thanks for having me, Jeremy.

Glaser: Let's start with your overall take on valuation. At these levels, should investors start getting worried that the market is just too pricey right now?

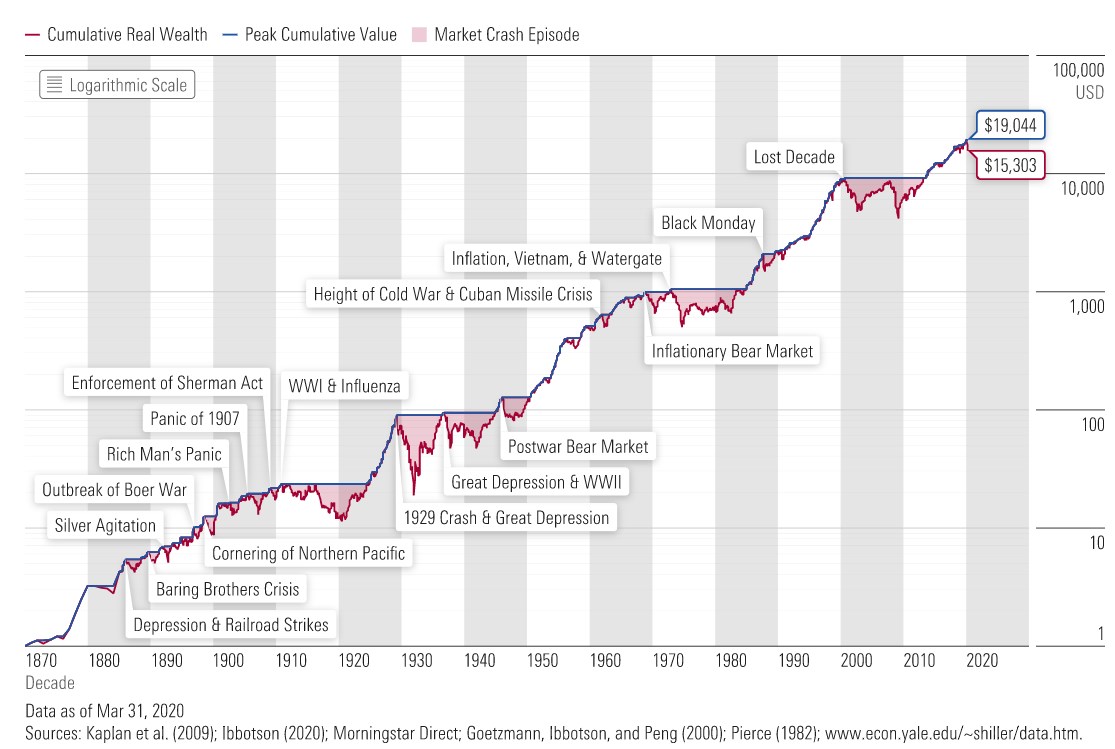

Coffina: One metric that I've been looking at a lot recently is the Shiller price-to-earnings ratio, and this metric uses 10-year average of real GAAP earnings in the denominator. The advantage is that it's been much more predictive historically of future total returns than one-year price-to-earnings ratios, which really hold little to no predictive value. A one-year price-to-earnings ratio will tell you, for example, that the valuation looked in line with historical norms right up to the financial crisis, and then it actually peaked in late 2009, after the recovery was already well under way.

In contrast, the Shiller price-to-earnings ratio was at relatively high levels, about the 80th percentile relative to the last 25 years, or in other words, it had been lower 80% of the time in the lead-up to the financial crisis. And then in the depths of the financial crisis in late 2008 and early 2009, the Shiller price-to-earnings ratio was seeing levels that it hadn't seen in 20-plus years.

So, the Shiller P/E tends to be a lot more predictive of future total returns, and that measure right now is at about 26, which is about the 68th percentile relative to the last 25 years. So, in other words, the market has in general been cheaper, based on this measure, 68% of the time since the late 1980s. That's certainly a cause for concern based on recent history.

First of all, the Shiller P/E has generally been much higher than its historical levels over the last 25 years, versus say that the prior 100 years. But a lot of the last 25 years, the market has actually have been materially overvalued. So, I'm thinking of the late '90s and the lead-up to the dotcom crash, and much of the mid-2000s and the lead-up to the financial crisis--all those numbers are in there in the historical data, and those obviously didn't end well for investors.

So, what we've seen historically is that any time the Shiller P/E is above, say, 25.5, which is about the 60th percentile relative to the past 25 years, subsequent total returns for investors have been very poor, on average in the low-single digits, with some very severe drawdowns, and pretty much the only time investors have achieved an attractive total return from current valuation levels is if it was at the beginning of a speculative bubble. So, say, 1996 before the late '90s bull market really got going, or 2002 and the lead-up to the housing bubble and the financial crisis. So, based on the Shiller P/E, I think there is definitely cause for concern from current valuation levels.

Glaser: So should investors then be preparing for a big sell-off, or a repeat of 2008?

Coffina: It's very, very hard to say. It's one thing to say that the market is richly valued relative to historical standards. It's a completely different thing to say that this means stocks are going to decline over the next one year, three years, or even five years. As I mentioned, in 1996 and in 2002, the S&P 500 was valued at similar levels and went on to have a great run over the next five years until it ended in a crash. So even over a time period as long as five years, saying that the market is relatively richly valued relative to history doesn't tell you much about what stocks are actually going to do in the near term.

I do think that there are sufficient opportunities out there to fill out a portfolio, but I do think investors need to be especially discerning in the current market environment--which is to say, they should focus on high-quality companies trading at reasonable prices, the same message that we're always pitching. But I think it becomes more important than ever in the current environment that, one, investors don't sacrifice quality in search of that outlier cheap stock, or on the other hand, that they don't pay up for quality and just pay any price at all.

We're still more or less fully invested in the Morningstar StockInvestor Tortoise and Hare portfolios at this point. We have very little cash in the Hare, a little less than 6% in the Tortoise, so I'm comfortable with the holdings that we have. But I think investors should moderate their expectations for future total returns.

I would definitely bet a million dollars to anyone who wants to take it that the market won't return 20% a year over the next five years, more or less like it did over the last five years. Current valuation levels just don't support that kind of total return going forward, and there's certainly the possibility of below-average total returns and perhaps even a severe drawdown at some point.

Glaser: Over the next 10 years, then, from these valuation levels, what kind of total return should investors be thinking about?

Coffina: Well, that's a great question, and I wish I had a better answer for you. It's going to largely depend on what happens to price-to-earnings ratios. I mentioned before that over the last 25 years, the Shiller P/E ratio took a big step up versus the prior 100 years. The measure used to be around 14-15. Over the last 25 years the norm has been more like 23-24. So anyone who is looking at a measure like this in, say, the early '90s would have decided that, say, 1992 was a great time to sell stocks, and they would have missed out on the '90s bull market, and even through the 2002 crash, they would have missed out on total returns in the high-single digits.

There's definitely a caveat to this whole kind of analysis; market conditions can change, and past is not necessarily a good indicator of what's going to happen in the future. In particular, in the environment that we're in right now, if interest rates stay as low as they are currently, that can certainly justify sustained higher valuation levels going forward. I'm not saying that's going to happen, but it's certainly possible.

I think if the Shiller P/E stays about where it is, then we can look forward to long-run returns, 10-plus years into the future, in line with the growth in real earnings per share, as well as current dividend yields. The current dividend yield on the S&P is a little under 2%. Historically, Shiller earnings, the denominator in the Shiller P/E, have grown at about 6% nominally and maybe about 3.5% in real terms.

I would assume probably inflation is going to be a little lower going forward than what we've seen over the last 20-25 years. So, if we assume 2% inflation, that would put real returns somewhere in the neighborhood of 4.5% to 6% and nominal returns with that 2% inflation, somewhere in the neighborhood of 6.5% to 8%. That would be my base case expectation: 6.5% to 8%, but again that relies on the price-to-earnings ratio remaining relatively stable.

If the price-to-earnings ratio continues to expand from here, as it has over the last five years, then you could expect returns substantially above that 8% number. If the P/E were to revert to historical norms, or even be lower than that, then you could expect returns probably below that 6.5%. But just setting an expectation, I'd say 6.5%-8% nominal, 4.5%-6% real, would be a decent number.

Glaser: Matt, thanks for your update on valuations today.

Coffina: Thanks for having me, Jeremy.

Glaser: For Morningstar, I'm Jeremy Glaser. Thanks for watching.